Category: Videos

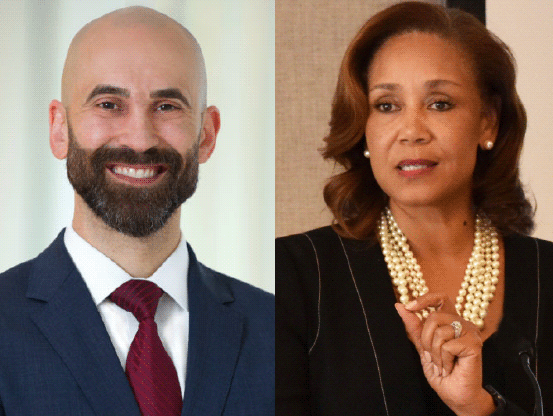

Building trusting relationships by using the right language

Philip Alberti, PhD, Founding Director of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Center for Health Justice, and Pamela Browner White, Chief Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Officer and Senior Vice President of Communications at ABIM and the ABIM Foundation, discussed the AAMC’s new Center for Health Justice, which was created in 2021 to address health inequities and improve community health across the US.

Philip also offers insight into the newly developed health equity communication guide, which was published jointly by the AAMC Center for Health Justice and the American Medical Association to support clinicians’ conversations with patients. The comprehensive guide promotes a deeper understanding of equity-focused, first-person language and why it matters. Philip and Pamela discussed why this language is so important in building trusting relationships and its impact in delivering equitable care for all.

Clips

Previous Webinars:

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Learning Network Webinar Series: Providing support following a patient harm event

Thomas H. Gallagher, M.D., general internist, Associate Chair for Patient Care Quality, Safety, and Value, and Professor at the University of Washington, and Carole Hemmelgarn, MS, MS, Senior Director of Education for the MedStar Institute for Quality & Safety, and Senior Director for the Executive Master’s program for Clinical Quality, Safety & Leadership at Georgetown University discussed how UW Medicine’s Communication and Resolution Program (CRP) seeks to provide support for patients, families, and involved clinicians following a patient harm event by promoting empathic, transparent, and ongoing communication about what happened and what patients and families most need in its wake.

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Conversation Series: Trauma and healing in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic

Kathleen Noonan, CEO of the Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers, and Daniel Wolfson, MHSA, executive vice president and COO of the ABIM Foundation, discuss trust and its relationship to trauma and healing in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Previous Webinars:

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Patient Advocate Spotlight: Tara Montgomery

Tara Montgomery is a trusted change leadership advisor and strategist who strives to connect the dots between healthy people and healthy democracies, bringing consumer and citizen perspectives to conversations about culture change in health care and other complex systems. Tara is driven by optimism about the power of collaboration to solve the world’s most challenging problems, having spent over two decades convening and partnering with US, UK, and international academic, cultural, scientific, and nonprofit institutions and leading strategic initiatives to advance public health, education, corporate social responsibility, and social change.

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Patient Advocate Spotlight: Dave Ellis

Dave Ellis is a national leader in providing trainings and facilitating conversations on the lasting impacts of ACEs and generational trauma. He shares his expertise with the State of New Jersey and coordinates statewide work related to ACE’s.

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Learning Network Webinar Series: Developing strategies to make care more affordable

Dr. Reshma Gupta and September Wallingford from Costs of Care shared information about the Patient Affordability Framework. This framework helps health systems and care teams develop strategies to make care more affordable for patients and avoid financial harm. Renee Firato, a patient affiliated with Family Reach, a nonprofit organization that provides financial support for families facing cancer, was our patient reactor.

Dr. Reshma Gupta, MD, MSHPM is a practicing internist, the Chief of Population Health and Accountable Care at University of California Davis Health in Sacramento, CA, and part of the Population Health Leadership Team for strategy across all UC Health campuses.

Dr. Gupta’s work focuses on innovation in policy and care redesign to improve the delivery of high-quality, affordable, equitable healthcare for patients and healthcare systems.

September Wallingford, RN, MSN is the Operations Director for Costs of Care. She oversees Costs of Care’s vast portfolio of programs dedicated to improving the value and affordability of healthcare and has led multiple grants and subcontracts from various organizations, as well as developed partnerships with leading healthcare organizations such as The Leapfrog Group, Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), and the ABIM Foundation. Ms. Wallingford is a practicing medical/surgical oncology nurse at a large academic medical center in Boston, Massachusetts and brings significant interprofessional insights to the Costs of Care team.

Renee Firato, Young Adult Leukemia survivor, current Adult Breast Cancer patient, Single supermom to 8 year old Ava. Preschool Teacher, Writer, Artist, Warrior, Advocate, Passionate about making the cancer experience better for all patients.

Previous Webinars:

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

Shantanu Nundy, MD, MBA, chief medical officer of Accolade, and Richard J. Baron, MD, president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine and the ABIM Foundation, discuss distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care after COVID-19.

Read Shantanu Nundy’s blog post: How COVID-19 may be the catalyst we need to accelerate trust in medicine

Previous Webinars:

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

Claire is a federal policy analyst and patient advocacy blogger whose health history goes back to the early 1980s. Since then, she has managed a raft of serious conditions, both acute and chronic. She has also been a caregiver for both chronically ill and terminally ill family members. A few years ago, she realized that her experience with healthcare could be used to help patients, so she started a blog and started looking for ways to use her skills to make positive changes to the healthcare ecosystem. Claire has a BA in Government from Smith College and an MA in Political Management from George Washington University.

You can reach Claire Sach’s blog here.

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

Alma McCormick is a member of the Crow Nation and the Executive Director of Messengers for Health, a Crow Indian 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization located on the Crow reservation in Montana. Alma is a leader and a community activist for improved health and wellness amongst her people. Her educational background is in Community Health and she furthered her education receiving a Bachelor’s of Science in Health and Wellness at the Montana State University-Billings. She has been actively involved in cancer awareness outreach and advocacy amongst Native American women in Montana since 1996. She has extensive experience in conducting community-based participatory research projects addressing various health needs of the Crow people while working in partnership with Montana State University-Bozeman. She has traveled nationwide to present at health conferences to share the program’s successes. She has also co-authored numerous peer reviewed journal articles. Alma’s passion for her work in community outreach stems from her personal experience of losing a young twin daughter to neuroblastoma cancer in 1985.

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust

Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

Janice Tufte resides in Seattle and is a patient collaborator involved with health systems research, evidence production, clinical practice quality improvement and human readable digital informed knowledge generation. She recently co-authored a paper currently under review with the Journal of Health Design that discusses the importance of collectively designing research and is working with AcademyHealth’s Paradigm Project in developing a new research prototype. Learn more about Janice at www.janicetufte.com.

- Conversation Series: Distributed, decentralized and digitally-enabled care

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Claire Sachs

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Alma McCormick

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Janice Tufte

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Susan Perez

- Patient Advocate Spotlight: Gwen Darien

- Public Agenda is building trust with patients

- Conversation Series: COVID-19’s impact on trust

- Introducing the Building Trust Initiative

- Vaccine hesitancy impacts on state and local vaccine planning

- Enhancing Influenza and COVID19 caccine uptake

- Tools for building institutional trust