Tag: COVID

The true impact of DEI in health systems

The responses to the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 have many lessons for health equity and the need for health systems to demonstrate a commitment to trustworthy processes and outcomes for people. I would like to dedicate this post to the memory of Dr. Francisco Marty, who embodied the values and behaviors that are needed to achieve equity within health systems.

An infectious disease physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Dr. Marty led the trial for the anti-viral medication Remdesivir at our hospital, which was one of the few options for treatment that existed at the start of the pandemic. Dr. Marty spent hours upon hours working with a multicultural, diverse team to make sure that all hospitalized people had access to accurate information and an opportunity to participate in the trial at our hospital, regardless of their race, ethnicity, age, disability status, or their languages spoken.

After reviewing the data for participation after the conclusion of the trial, we found that Dr. Marty succeeded in enrolling a diverse group of people to receive this important care. Without his commitment to ensuring that trial participants were represented fairly and equally, many may not have had the chance to participate simply because of the color of their skin or their age.

As we reflect on what is needed to build trustworthy health systems, it is important to note that structural changes are needed, including better systems for data collection and addressing social determinants of health. The work of incredible individuals like Dr. Marty also demonstrate that diversity, equity, and inclusion in health systems is deeply impactful and an important strategy for achieving trustworthy care.

Cheryl R. Clark MD, ScD is a hospitalist and health equity researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Clark’s research focuses on social determinants of health as contributors to health status and utilization in the U.S..

59% of U.S. adults say health care system discriminates at least “somewhat,” negatively affecting trust

ABIM Foundation’s new ‘Building Trust’ effort will look at increasing equity and reducing systemic racism in U.S. health care

A clear majority of adults say the U.S. health system routinely discriminates, according to a survey conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago. Fifty-nine percent (59%) of adult consumers say the health care system discriminates at least “somewhat,” with 49% of physicians agreeing.

About one in every eight adults (12%) say they have been discriminated against by a U.S. health care facility or office, with Black individuals being twice as likely to experience discrimination in a health care facility compared to white counterparts. The survey shows that experiences of discrimination affect trust in U.S. health care. People who report being discriminated against in a health care setting are twice as likely to say they do not trust the system.

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation is spearheading the Building Trust initiative, a national effort to focus on building trust as a core organizational strategy for improving health care. It is working collaboratively with all health care stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, system leaders and others. Nine years ago, the ABIM Foundation created the Choosing Wisely initiative, which was nationally recognized for promoting conversations between patients and their clinicians about curbing the overuse of unnecessary medical care.

Health care stakeholders must collaborate to identify and address contributors to bias, which worsen health outcomes, especially for people of color.

Richard J. Baron, MD, President and CEO of the ABIM Foundation

“Just like the deep impact of systemic racism being felt in all aspects of society, any form of discrimination fuels mistrust between patients and the health care system patients rely on to treat them,” said Richard J. Baron, MD, president and chief executive officer of the ABIM Foundation. “Health care stakeholders must collaborate to identify and address contributors to bias, which worsen health outcomes, especially for people of color.”

Apart from gaps in trust in the health care system, instances of discrimination are similar when looking at relationships between individual patients and their doctors. About one in eight patients (12%) say they have experienced discrimination by a doctor, with Black individuals being almost twice as likely as the general population to report discrimination by a doctor. More than one in five Black patients (21%) report discrimination by a doctor, versus 11% of Hispanic adults and 8% of Asian adults.

Although the survey shows patients and physicians enjoy mutually high levels of trust with each other overall, Black and Hispanic adults are significantly less likely to say their doctors demonstrate trust-building behaviors. For example, 86% of white adults say they believe their physicians trust what they say, compared to 76% of Black adults and 77% of Hispanic adults. Eighty percent (80%) of white patients say their doctor spends an appropriate amount of time with them, compared to 68% of Hispanic adults and 73% of Black adults. Seventy-seven percent (77%) of white adults say their physician cares about them, compared to 67% of Hispanic adults and 71% of Black adults.

Patients, clinicians and system leaders all want more equitable care and better outcomes, and part of the solution lies with increasing trust.

Daniel Wolfson, EVP and COO of the ABIM Foundation

“Achieving greater equity and less discrimination in health care requires more understanding about what it takes to build truly trusting relationships,” said Daniel Wolfson, executive vice president and chief operating officer of the ABIM Foundation. “Patients, clinicians and system leaders all want more equitable care and better outcomes, and part of the solution lies with increasing trust.”

Despite a clear majority of patients believing discrimination in health care is common, the survey shows 81% of physicians give their employer a good grade—either an A or B—in their efforts to address health equity. Physicians say they are optimistic that their health system will improve diversity and equity in the next five years. Sixty-two percent (62%) say their own health system will improve equity in patient outcomes in the next five years. More than half of physicians (56%) believe diversity in the physician workforce will improve over the next five years. Fewer physicians (49%) think diversity in health system leadership will improve over the same period.

The NORC research is comprised of two surveys, one with physicians and one with consumers. The physician survey is a non-probability sample of 600 physicians. The consumer survey is a probability-based sample of 2,069 respondents with oversamples for Black, Hispanic and Asian respondents and has a margin of error of +/- 3.15 percentage points. Surveys were conducted between Dec. 29, 2020, and Feb. 5, 2021. Last month the ABIM Foundation released research demonstrating diminished trust among physicians and consumers in health system leaders and government agencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Poll: Physicians’ trust In health system leadership declines during COVID-19 pandemic

ABIM Foundation leads effort on “Building Trust” among health care stakeholders

Significant gaps in how physicians and patients view trust

New research shows a significant decline in physicians’ trust in leaders of health care systems during the COVID-19 pandemic, and notable differences between how physicians and the public perceive trust in U.S. health care. The research was conducted for the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation by NORC at the University of Chicago.

The ABIM Foundation released the research to coincide with the launch of Building Trust, a national effort that focuses on increasing trust among health care stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, system leaders, researchers, and others. Nine years ago, the ABIM Foundation created the Choosing Wisely initiative, which was nationally recognized for promoting conversations between patients and their clinicians about curbing the overuse of unnecessary medical care.

In a year of unprecedented pressure on health care, nearly one in three physicians surveyed (30%) say their trust in the U.S. health care system and health care organization leadership decreased. Only 18% report increased trust.

Health care is fundamentally grounded in a series of human relationships, and the strength of those relationships determines how well health care works

Richard J. Baron, MD

This is in stark contrast to the overwhelming trust physicians have in their fellow clinicians. Physicians report high levels of trust for other physicians and nurses (94% trusting doctors within their practice; 85% trusting doctors outside of their practice; and 89% trusting nurses)—but only two-thirds (66%) trust health care organization leaders and executives. During the pandemic, physicians report increased trust for fellow physicians (41%) and for nurses (37%).

“Health care is fundamentally grounded in a series of human relationships, and the strength of those relationships determines how well health care works,” said Richard J. Baron, MD, president and chief executive officer of the ABIM Foundation. “The pandemic bolstered trust among clinicians, but intensified physician mistrust of health care organizations. American health care has a trust problem and rebuilding it is essential.”

Overall, 78% of people say they trust their primary doctor. Significant differences exist, however, between different groups of people, with older adults (90%), white people (82%), and high-income individuals (89%) being much more likely to say they trust their doctors. Among people who report lower trust in their doctors, 25% said their doctor spends too little time with them and 14% said their doctor does not know or listen to them.

The survey shows stark differences in how physicians and patients view aspects of a medical appointment that affect trust. Nearly all physicians (90%) believe patients can easily schedule appointments, but nearly one in four patients (24%) disagree. Almost all physicians (98%) say that spending an appropriate amount of time with patients is important, but only 77% of patients think their doctor spends an appropriate amount of time with them.

In spite of these trust gaps, consumers trust clinicians—doctors (84%) and nurses (85%)—more than the health care system as a whole (64%). About one in three consumers (32%) say their trust in the health care system decreased during the pandemic, compared to 11% whose trust increased.

Trust is an essential part of medical professionalism and ultimately contributes to better patient outcomes.

Daniel Wolfson

The survey shows that government agencies have trust-building work to do. The research reveals that 43% of physicians say their trust in government health care agencies decreased during the pandemic.

“Trust in organized institutions has been declining for years and health care is not immune,” said Daniel Wolfson, executive vice president and chief operating officer of the ABIM Foundation. “Building trust requires engaging stakeholders across the health care spectrum to better identify what’s happening and share practices that increase trust between different parties. Trust is an essential part of medical professionalism and ultimately contributes to better patient outcomes.”

Focus areas for the ABIM Foundation’s Building Trust initiative include increasing relational and organizational trust, increasing equity and reducing systemic racism in U.S. health care, and the imperative of trusting science and facts, free from politics.

Leaders from all parts of the health care ecosystem will come together through the multi-year initiative to discuss how to elevate trust in health care. The effort will include significant research, dialogue and experimentation involving all parties.

A key component will be a Trust Practices Network that identifies, tests, and shares practices with the goal of building trust between health care stakeholders. The practices include interventions like:

- SCAN Health’s use of a peer advocate program to build caring relationships with plan members and encourage them to receive needed care;

- Northwestern Medicine’s African American Transplant Access Program, which strives to build trust with Black patients and increase the likelihood they will seek needed transplants and complete the necessary evaluation to be included on the transplant waiting list; and

- Scripps Clinic’s “One Thing Different” program, which gives staff and physicians the autonomy to do one thing of their own choosing to make a difference in the lives of their patients, relying on self-reflection and soul searching to improve care and enhance trust between staff and leadership.

More than 50 organizations have already contributed trust-building practices.

The NORC research was conducted between Dec. 29, 2020 and Feb. 5, 2021. The physician survey is a non-probability sample of 600 physicians. The consumer survey is a probability based sample of 2,069 respondents with oversamples for Black, Hispanic, and Asian respondents and has a margin of error of +/- 3.15 percentage points.

This is not a safe space: trust and inequities in the time of COVID-19

During a late-night shift in the Emergency Department (ED) in April, I took care of Mr. S, a man in his early twenties who presented with a sickle cell vaso-occlusive crisis. COVID-19 testing had returned negative. The carefully composed steps in his hematology care plan had begun to ease his pain. Yet his oxygen levels were hovering just below a safe level for discharge. In addition to further workup, he would need to stay the night, at least while requiring oxygen. Mr. S asked me to call his parents who could not visit him in the ED. They would not be pleased, he warned me; they wanted him home. After discussing the difficult balance of risks – those of staying in the hospital during the COVID surge or going home without oxygen – Mr. S and his parents ultimately agreed to him staying overnight. Even so, Mr. S’s father’s parting words were “if my son gets COVID in the hospital, it’s on you.” These words and the profound distrust they conveyed echoed in my head throughout the evening.

A few weeks later, on a late Friday afternoon during my telemedicine clinic, Mr. J was describing by phone what could have been a gout flare in his knee or, far more troubling, a case of septic arthritis. After staffing with my attending, I explained my concerns to Mr. J and recommended he go to the ED. I talked him through the new layout and triage process. Unlike Mr. S’s family, I knew Mr. J well – I had taken care of him in inpatient and outpatient settings since I was an intern. An elderly man from Puerto Rico, his experiences with gang-related violence decades ago had left him with PTSD, depression, and severe anxiety. When I told him I was graduating from residency, he said he wanted to give me one of his late mother’s rosaries. By Monday, he had not visited the ED and I reached back out. He said he simply could not overcome the fear of getting COVID-19. The red-hot pain, redness, and swelling in his knee had fortunately resolved over the weekend. For Mr. J, his distrust in the hospital’s ability to keep him safe superseded the trust we had each built over the course of three years.

I fear that for people who have experienced medical bias or substandard care in the past, concerns about safety within the hospital space could pose devastating barriers to care

Mr. S and Mr. J are both affected by multifold inequities in our health system, Mr. S as a Black man with sickle cell disease and Mr. J as a Latino man with mental health problems. They both come from neighborhoods that were hotspots for COVID-19 and had carefully avoided infection. Personal and institutional distrust affected the way they navigated non-COVID care within a pandemic-era hospital system and how they interacted with me, a white trainee. Concerns about infection likely shape every patient’s decision-making about visiting hospitals now. However, I fear that for people who have experienced medical bias or substandard care in the past, concerns about safety within the hospital space could pose devastating barriers to care. Learning about the mortality disparities in COVID-19 further validates distrust. Ongoing research has begun to examine decreases in standard care services provided during the pandemic [i],[ii]. A focus on inequities must inform this research. Interventions to address the findings must emphasize safety and trust in marginalized communities; for example, by providing more community-embedded services.

At every turn in the way the COVID-19 pandemic has played out, the American medical community has only retroactively recognized the inequities that compound each other to lead to Black and Brown people dying at much higher rates than their white counterparts. We must probe beyond the COVID-19 diagnosis to fully understand inequities in pandemic-era care.

Alyse Wheelock is a first-year fellow in Infectious Diseases at Boston Medical Center, where she also completed internal medicine residency.

[i] Garcia S, Albaghdadi MS, Meraj PM, et al. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020 April 9

[ii] Lange SJ, Ritchey MD, Goodman AB, et al. Potential Indirect Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Use of Emergency Departments for Acute Life-Threatening Conditions — United States, January–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:795–800. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6925e2external icon

The virus does discriminate

“The virus does not discriminate,” the infectious disease experts told us. As the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States, that warning was issued with the best of intentions. If you search for that phrase today on Twitter, you’ll find the message being repeated, as public health officials implore all Americans to protect ourselves and others from the latest surge in cases of COVID-19.

From my home in Brooklyn, an early epicenter of the pandemic, it didn’t take long to wonder if something was awry with that message. At every turn, our understanding of COVID-19 and our response to it have been complicated by mixed and misleading messages. Science denial and political motives have introduced misinformation. At the same time, rapid shifts in evidence and knowledge have required new policies and messages. The combination of bad faith and emerging science has muddled public understanding and fueled mistrust. For some of us, mistrust is deeply self-protective. A history of medical exploitation and the systematic denial of access to the opportunities and social conditions that determine health gives millions of Black Americans cause to doubt that their lives really matter.

From mid-March through mid-April, as I sheltered safely in my apartment in one of New York City’s whitest, most affluent neighborhoods, I listened with fear and grief to the round-the-clock sirens from ambulances carrying COVID-19 patients to our local hospital. Yet few of my neighbors were among them. Apart from those who are frontline health care professionals, the majority of my neighbors are not essential workers. They aren’t riding the subway to work. Most of my neighbors, based on their demographics, are the kind of people who have good health insurance and paid vacation and sick days and cars and gym memberships and healthy food deliveries. There’s a good chance that they don’t know anyone who has been incarcerated. It’s unlikely they have had negative experiences with the police or medical professionals.

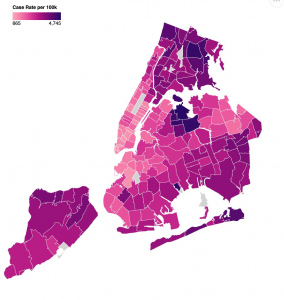

When New York City started to release data on COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by race and ethnicity (in April) and then by zip code (in May), the zip code covering most of my neighborhood (11215) stood out on the color-coded map as a poignant patch of pale pink, representing the lowest infection rate in Brooklyn. I don’t know if the graphic designers chose this palette intentionally, but its symbolism was not lost on me. In New York, the impact of the virus on people of color and residents of majority-Black and Latinx zip codes has been particularly devastating. Our COVID-19 maps paint a graphic picture of Blackness as a co-morbidity here and across America (when data is made available—a problem in itself). They awaken my understanding of why so many people cannot trust experts. The experts were wrong: the virus does discriminate. The virus discriminates not because of biology, but because we as a society allow it to. They deepen my understanding of why so many people do not trust our country’s leaders. If we cannot trust in our systems to protect our most vulnerable people from a pandemic virus, we cannot trust them at all.

For several years, I’ve been participating in efforts to help build and rebuild trust in health care. Most of my work on trust has been at the levels of interpersonal relationships, team behaviors, and organizational cultures. When I’ve looked at the systemic level, the focus has leaned towards effective public engagement or solutions for repairing the health care system itself. We’ve assumed in good faith that if we rebuild trust in health care piece by piece and publish enough respectable articles about best practices and the role of professionalism, we will catalyze change. Those strategies are still meaningful, but they aren’t enough anymore. COVID-19, with its devastating impact on Black and Brown people, is evidence enough that wider systems of injustice in America not only drive bad health outcomes but also betray our founding values. What if we admit that the distrust in our country’s institutions is warranted? What if we accept that our failure to mitigate COVID-19 is not only a consequence of inequities in our health care system, but is so enmeshed in systemic injustice that we cannot fix it as if it were a quality improvement initiative?

By June, Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, the gateway for thousands of ambulances on their final approach to our local hospital, had become the gateway for thousands of mask-wearing protestors to join the Black Lives Matter marches. When the sound of sirens was replaced by the sounds of chanting and police helicopters, it was a call to action for all of us who are serious about rebuilding trust. It demands that we listen better. Health equity cannot happen until we reckon with systemic racism. Trust cannot be won until we earn it at the most fundamental level. If we want to do better, we need to rise to the challenge of rebuilding our country based on social, racial, and economic justice. It may feel uncomfortable to those of us who have spent our lives believing that professionalism required us to politely avoid crossing the boundary between science and politics. But the pandemic compels us to do just that. It’s time for physicians and health care leaders to use our privilege to dismantle the unhealthy systems that undermine our national wellbeing. This is how we will earn trust.

Tara Montgomery is Principal at Civic Health Partners, an organization she founded after 15 years leading Health Impact at Consumer Reports. As a coach, speaker, and writer, she guides leaders through the discovery of ethical solutions and trust-building strategies that integrate empathy and evidence.

Amidst the pandemic, building trust between patients and health care providers

COVID-19 has exposed many frailties in the American health system but has it done some good for Americans’ attitude towards it? A recent Gallup poll shows that over 90% of Americans approve of health care providers’ handling of the COVID-19 response. With daily evening cheers and other signs of enthusiastic support, Americans’ support for health care professionals may be at an all-time high. While Americans may praise the efforts of individual caregivers amidst the pandemic, we know from survey research that Americans’ trust in the health care system has been eroding for many years. If we hope to maintain this newfound appreciation for health care providers, we must take a good look at our system and how we can create an environment conducive to trust.

The ABIM Foundation’s Building Trust initiative seeks to elevate the importance of trust as an essential organizing principle to guide operations and improvements in health care. To support the initiative, Public Agenda has conducted interviews with several consumer and patient experts and advocates about opportunities they see for advancing trust in health care. This will provide the initiative with actions and practices that promote patient trust in their clinicians and the health care system.

One theme that has emerged so far in the interviews is the importance of ensuring that health care facilities are truly accessible. It is hard to trust someone if they don’t devote effort to making their space accommodating to you. Maya Sabatello LLB, PhD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Bioethics in the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons with decades of experience as a disability rights advocate and scholar says that we need to confront our “generalization of needs” concerning accessibility. “The ramp isn’t enough,” she says. “It doesn’t help a deaf person. Think about the postings in medical institutions. They rarely include braille.” These physical barriers can make patients with disabilities feel unwelcome and reinforce the exclusion they may experience from society at large.

Even if people aren’t overtly experiencing discrimination, they are still guarded.

Kellan Baker, MPH, MA

Another theme that has emerged is the need to not only remove physical barriers but actively create welcoming spaces for marginalized patients. Kellan Baker, MPH, MA is the Centennial Scholar in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. As a transgender man, he can attest to the pervasive discrimination that LGBTQ people, especially transgender people face, even in health care settings. “Even if people aren’t overtly experiencing discrimination, they are still guarded.” Baker says that to create trust, robust nondiscrimination policies must be created and prominently displayed in the waiting room area. He also noted the need for respectful and inclusive data collection in healthcare settings about patients’ sexual orientation and gender identity. Health care staff must also know how their behavior creates either a welcoming or hostile environment. “Cultural competency training [must] be made available not only to providers, but to all staff who patients may interact with.”

Over the coming months, the ABIM Foundation, Public Agenda, and the National Patient Advocate Foundation will be diving deeper into this question of what it takes to build sustained trust in the health care system from the perspective of patients, consumers and caregivers. To inform this work, we’ll be talking with many other stakeholders about what’s working all over the country and what people want to try. As we step into an uncertain future with COVID-19, this knowledge can help us meet the challenges of the pandemic and understand how to seize the opportunities to build greater trust.

Treston Codrington is the Public Engagement Associate at Public Agenda. He is a writer, community organizer, and proud native of Brooklyn, New York. With a wealth of local and international engagement experience, his goal is to bridge the divide between communities, scientists, and policy-makers and help facilitate co-productive processes with these stakeholders to improve our world.

Matt Leighninger leads Public Agenda’s work in public engagement and democratic governance and directs the Yankelovich Center for Public Judgment. Matt is a Senior Associate for Everyday Democracy and serves on the boards of E-Democracy.Org, the Participatory Budgeting Project, the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2USA), and The Democracy Imperative. In the last two years, Matt developed a new tool, Text, Talk, and Act, that combined online and face-to-face participation as part of President Obama’s National Dialogue on Mental Health. He is author of The Next Form of Democracy (2006) and co-author of Public Participation in 21st Century Democracy with Tina Nabatchi.

Trust as an antidote to the viral spread of medical misinformation

The existence of medical misinformation is palpable for anyone scanning recent news headlines. Journalists and commentators often point to the spread of misinformation as a regular aspect of contemporary life, as we have seen in reporting on the novel coronavirus, which causes COVID-19. Faced with emerging and continued threats to public health and the simultaneous specter of patients being misled by misinformation, some health care professionals are frustrated and wonder what they can do to help.

At Duke University, I recently spent time talking with health care professionals in a workshop for the Duke AHEAD program that I organized with Dr. Jamie Wood, a medical education faculty member at Duke’s School of Medicine. Many participants had stories to tell about patient encounters with misinformation. Participants also were eager to talk about hypothetical scenarios we introduced as prompts to consider how we might optimally talk with patients about misleading information they reference, e.g., regarding an untested treatment for cancer.

We do not have the time or resources to argue against every false claim to which patients are exposed, but we do have opportunities to build and reinforce trust by acknowledging and listening to patients.

In many instances, health care professionals’ first response is to generate a reasonable counterargument regarding misinformation, e.g., “my argument to them would be…” That well-intentioned response to patients, however, misses an important opportunity that could be central to our systemic response to the spread of medical misinformation.

What if our first response to patients who reference clearly problematic claims was to ask: “Why are those claims important to you, and what concerns or questions do you have about your health?” We do not need to validate false claims in order to acknowledge and validate our patients’ interest in well-being. If we can take a deep breath and focus on listening rather than counterarguing, we often can find opportunities to redirect patients to credible sources of information.

At a system level, we also could better monitor patient encounters with misinformation and develop easily accessible information sources that respond to the questions those encounters raise, rather than simply bemoan the falsehoods. We could be systematically tracking patient questions and learning from those questions to craft educational resources for communities. In this way, patient encounters with sensational misinformation could help crystalize their questions and concerns (even if at the same time also offering a frustrating distraction), which means that with the right monitoring and learning tools we could improve patient health education.

We do not have the time or resources to argue against every false claim to which patients are exposed, but we do have opportunities to build and reinforce trust by acknowledging and listening to patients. Such trust could inoculate against future acceptance of medical misinformation by encouraging conversations. From this perspective, patient references to misinformation in the clinic can be a victory of sorts if we consider that the alternative is patient refusal to show up at all or reluctance to mention their concerns in the first place.

Brian Southwell is Senior Director of the Science in the Public Sphere program at RTI International and Adjunct Professor and Duke-RTI Scholar at Duke University. He has written and edited numerous articles and books on misinformation and public understanding of health, including Misinformation and Mass Audiences (University of Texas Press). He also hosts a public radio program called The Measure of Everyday Life for WNCU.