Author: Tara Montgomery

Why standards matter

As medicine becomes politicized, trust in our physicians matters more than ever. High professional standards help them earn it.

“How can I find a doctor I can trust?” I keep hearing this question—from those feeling confused about a vaccination decision to those looking for an ob/gyn who shares their personal values. There’s unprecedented angst, uncertainty, and mistrust. During two decades as a patient and citizen advocate, I’ve encountered the mistrust that arises when systems that are supposed to protect us cause harm. I’ve learned that trust is an asset our health system cannot do without. It is at the heart of our relationships with our physicians and care teams and an essential foundation for the institution of medicine. Yet as our social fabric continues to fray, even the most trusted relationships come under strain. Our relationships with our physicians feel more fragile when the practice of medicine is politicized, and misinformation compounds our uncertainty and confusion about our health choices.

As an independent volunteer public (non-physician) member of the Board of Directors of ABMS (the American Board of Medical Specialties), a nonprofit organization that oversees the standards for physician certification across 24 medical specialties (the American Osteopathic Association is another), I have a window into what happens inside the network of institutions that oversee the practice of medicine in the United States. The medical profession is dealing with its own trust challenges as it negotiates the tensions between freedom, regulation, and professionalism. In recent months, certifying boards have taken further steps to uphold their accountability by addressing unprofessional behavior and pledging to withdraw or deny certification to physicians who publicly share information that is directly contrary to the prevailing medical evidence.

While some physicians are uniting to defend their ability to take care of their patients and protect those patients’ reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy, others are asserting a questionable freedom to prescribe unproven treatments or disseminate misinformation that leads to medical harm or death. Some physicians are rejecting the institutions that enact and enforce standards of performance and conduct and oversee physicians’ accountability to the public. Efforts by these institutions to overcome mistrust should be welcomed. Self-regulation is a privilege that makes physicians accountable to their peers and importantly, the public. It is grounded in a set of agreed-upon standards and behaviors based on a common set of values and ethical commitments. It represents a social contract between physicians and the community that includes a promise to put the interests of patients first.

But when mistrust in institutions manifests itself as legislative interference in that professional self-regulation, the politicization of the practice of medicine becomes an assault on medicine itself. The assault is already happening in states where state legislatures have told the state boards that license and regulate physicians that they may not take disciplinary action against physicians who disseminate misinformation or disinformation about COVID-19, vaccination, or scientifically valid treatments. The effects are harmful to physicians, nurses, and patients alike. In some states, physicians no longer have the freedom to provide the care they are trained to provide.

As patients, we are left wondering who we can turn to as trusted navigators as we make sense of our medical choices. As medicine becomes politicized, the answer to that initial question “How can I find a doctor I can trust?” is not as simple as reading patient reviews or going to a top-rated hospital. It’s important to know how to recognize a physician who has gone through rigorous and objective assessment of their knowledge, skills, judgment, and competencies.

The fourteen years I spent with the nonprofit Consumer Reports taught me to recognize a rigorous testing process and the ways it helps to build trust. That rigor is critical for the process of physician board certification. I’ve been reassured to find it at the American Board of Medical Specialties and its member boards: the research underlying every step, the collaborative process of standard-setting, the scientific methods that inform assessments, the secure examinations, the evaluation of ethics and professionalism, the verification that a physician is clear of any professional wrongdoing, the requirement to contribute to improving health and health care, and the cycles of continuing certification to stay current and maintain competency throughout a physician’s career. As a result, specialty board certification is one of the strongest signals that we can trust our physician. It represents a commitment to both learning and accountability.

Patients choosing a physician for themselves or loved ones would be wise to check online if a physician is currently board-certified. But if we want to help build a culture of trust in medicine, based on facts and not ideology, there are things we need to do as citizens to push back against the assault on the medical profession as well. We can communicate our support to elected representatives and candidates who oppose legislative interference in the practice of medicine and its self-regulation. As civic-minded community members, we can ask to be appointed as “public members” of the state boards that regulate medical practice or join a local hospital board as an advocate for patient safety and physician wellbeing. We can run for school boards where we can participate as champions of science education and children’s health. Civic engagement is as critical for building trust in medicine as it is for strengthening our democracy.

| This blog was originally posted by Civic Health Partners on January 19, 2023, and has been syndicated with permission. Tara Montgomery is Founder & Principal of Civic Health Partners, an independent coaching and consulting practice that helps leaders reflect on trust and develop public engagement strategies that are worthy of trust. She is a volunteer Public Member of the Board of Directors of the American Board of Medical Specialties. Tara serves on our Patient Advisory Committee which provides advice on how to educate and engage patients and caregivers about trust in health care. |

The virus does discriminate

“The virus does not discriminate,” the infectious disease experts told us. As the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States, that warning was issued with the best of intentions. If you search for that phrase today on Twitter, you’ll find the message being repeated, as public health officials implore all Americans to protect ourselves and others from the latest surge in cases of COVID-19.

From my home in Brooklyn, an early epicenter of the pandemic, it didn’t take long to wonder if something was awry with that message. At every turn, our understanding of COVID-19 and our response to it have been complicated by mixed and misleading messages. Science denial and political motives have introduced misinformation. At the same time, rapid shifts in evidence and knowledge have required new policies and messages. The combination of bad faith and emerging science has muddled public understanding and fueled mistrust. For some of us, mistrust is deeply self-protective. A history of medical exploitation and the systematic denial of access to the opportunities and social conditions that determine health gives millions of Black Americans cause to doubt that their lives really matter.

From mid-March through mid-April, as I sheltered safely in my apartment in one of New York City’s whitest, most affluent neighborhoods, I listened with fear and grief to the round-the-clock sirens from ambulances carrying COVID-19 patients to our local hospital. Yet few of my neighbors were among them. Apart from those who are frontline health care professionals, the majority of my neighbors are not essential workers. They aren’t riding the subway to work. Most of my neighbors, based on their demographics, are the kind of people who have good health insurance and paid vacation and sick days and cars and gym memberships and healthy food deliveries. There’s a good chance that they don’t know anyone who has been incarcerated. It’s unlikely they have had negative experiences with the police or medical professionals.

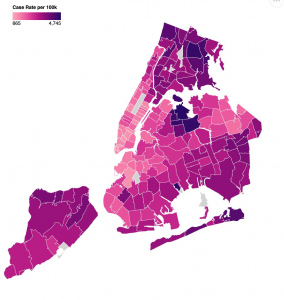

When New York City started to release data on COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by race and ethnicity (in April) and then by zip code (in May), the zip code covering most of my neighborhood (11215) stood out on the color-coded map as a poignant patch of pale pink, representing the lowest infection rate in Brooklyn. I don’t know if the graphic designers chose this palette intentionally, but its symbolism was not lost on me. In New York, the impact of the virus on people of color and residents of majority-Black and Latinx zip codes has been particularly devastating. Our COVID-19 maps paint a graphic picture of Blackness as a co-morbidity here and across America (when data is made available—a problem in itself). They awaken my understanding of why so many people cannot trust experts. The experts were wrong: the virus does discriminate. The virus discriminates not because of biology, but because we as a society allow it to. They deepen my understanding of why so many people do not trust our country’s leaders. If we cannot trust in our systems to protect our most vulnerable people from a pandemic virus, we cannot trust them at all.

For several years, I’ve been participating in efforts to help build and rebuild trust in health care. Most of my work on trust has been at the levels of interpersonal relationships, team behaviors, and organizational cultures. When I’ve looked at the systemic level, the focus has leaned towards effective public engagement or solutions for repairing the health care system itself. We’ve assumed in good faith that if we rebuild trust in health care piece by piece and publish enough respectable articles about best practices and the role of professionalism, we will catalyze change. Those strategies are still meaningful, but they aren’t enough anymore. COVID-19, with its devastating impact on Black and Brown people, is evidence enough that wider systems of injustice in America not only drive bad health outcomes but also betray our founding values. What if we admit that the distrust in our country’s institutions is warranted? What if we accept that our failure to mitigate COVID-19 is not only a consequence of inequities in our health care system, but is so enmeshed in systemic injustice that we cannot fix it as if it were a quality improvement initiative?

By June, Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, the gateway for thousands of ambulances on their final approach to our local hospital, had become the gateway for thousands of mask-wearing protestors to join the Black Lives Matter marches. When the sound of sirens was replaced by the sounds of chanting and police helicopters, it was a call to action for all of us who are serious about rebuilding trust. It demands that we listen better. Health equity cannot happen until we reckon with systemic racism. Trust cannot be won until we earn it at the most fundamental level. If we want to do better, we need to rise to the challenge of rebuilding our country based on social, racial, and economic justice. It may feel uncomfortable to those of us who have spent our lives believing that professionalism required us to politely avoid crossing the boundary between science and politics. But the pandemic compels us to do just that. It’s time for physicians and health care leaders to use our privilege to dismantle the unhealthy systems that undermine our national wellbeing. This is how we will earn trust.

Tara Montgomery is Principal at Civic Health Partners, an organization she founded after 15 years leading Health Impact at Consumer Reports. As a coach, speaker, and writer, she guides leaders through the discovery of ethical solutions and trust-building strategies that integrate empathy and evidence.