“The virus does not discriminate,” the infectious disease experts told us. As the COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States, that warning was issued with the best of intentions. If you search for that phrase today on Twitter, you’ll find the message being repeated, as public health officials implore all Americans to protect ourselves and others from the latest surge in cases of COVID-19.

From my home in Brooklyn, an early epicenter of the pandemic, it didn’t take long to wonder if something was awry with that message. At every turn, our understanding of COVID-19 and our response to it have been complicated by mixed and misleading messages. Science denial and political motives have introduced misinformation. At the same time, rapid shifts in evidence and knowledge have required new policies and messages. The combination of bad faith and emerging science has muddled public understanding and fueled mistrust. For some of us, mistrust is deeply self-protective. A history of medical exploitation and the systematic denial of access to the opportunities and social conditions that determine health gives millions of Black Americans cause to doubt that their lives really matter.

From mid-March through mid-April, as I sheltered safely in my apartment in one of New York City’s whitest, most affluent neighborhoods, I listened with fear and grief to the round-the-clock sirens from ambulances carrying COVID-19 patients to our local hospital. Yet few of my neighbors were among them. Apart from those who are frontline health care professionals, the majority of my neighbors are not essential workers. They aren’t riding the subway to work. Most of my neighbors, based on their demographics, are the kind of people who have good health insurance and paid vacation and sick days and cars and gym memberships and healthy food deliveries. There’s a good chance that they don’t know anyone who has been incarcerated. It’s unlikely they have had negative experiences with the police or medical professionals.

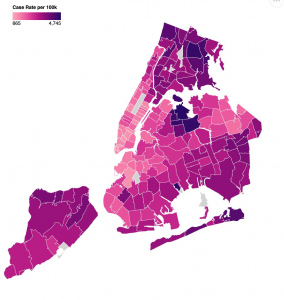

When New York City started to release data on COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by race and ethnicity (in April) and then by zip code (in May), the zip code covering most of my neighborhood (11215) stood out on the color-coded map as a poignant patch of pale pink, representing the lowest infection rate in Brooklyn. I don’t know if the graphic designers chose this palette intentionally, but its symbolism was not lost on me. In New York, the impact of the virus on people of color and residents of majority-Black and Latinx zip codes has been particularly devastating. Our COVID-19 maps paint a graphic picture of Blackness as a co-morbidity here and across America (when data is made available—a problem in itself). They awaken my understanding of why so many people cannot trust experts. The experts were wrong: the virus does discriminate. The virus discriminates not because of biology, but because we as a society allow it to. They deepen my understanding of why so many people do not trust our country’s leaders. If we cannot trust in our systems to protect our most vulnerable people from a pandemic virus, we cannot trust them at all.

For several years, I’ve been participating in efforts to help build and rebuild trust in health care. Most of my work on trust has been at the levels of interpersonal relationships, team behaviors, and organizational cultures. When I’ve looked at the systemic level, the focus has leaned towards effective public engagement or solutions for repairing the health care system itself. We’ve assumed in good faith that if we rebuild trust in health care piece by piece and publish enough respectable articles about best practices and the role of professionalism, we will catalyze change. Those strategies are still meaningful, but they aren’t enough anymore. COVID-19, with its devastating impact on Black and Brown people, is evidence enough that wider systems of injustice in America not only drive bad health outcomes but also betray our founding values. What if we admit that the distrust in our country’s institutions is warranted? What if we accept that our failure to mitigate COVID-19 is not only a consequence of inequities in our health care system, but is so enmeshed in systemic injustice that we cannot fix it as if it were a quality improvement initiative?

By June, Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, the gateway for thousands of ambulances on their final approach to our local hospital, had become the gateway for thousands of mask-wearing protestors to join the Black Lives Matter marches. When the sound of sirens was replaced by the sounds of chanting and police helicopters, it was a call to action for all of us who are serious about rebuilding trust. It demands that we listen better. Health equity cannot happen until we reckon with systemic racism. Trust cannot be won until we earn it at the most fundamental level. If we want to do better, we need to rise to the challenge of rebuilding our country based on social, racial, and economic justice. It may feel uncomfortable to those of us who have spent our lives believing that professionalism required us to politely avoid crossing the boundary between science and politics. But the pandemic compels us to do just that. It’s time for physicians and health care leaders to use our privilege to dismantle the unhealthy systems that undermine our national wellbeing. This is how we will earn trust.

Tara Montgomery is Principal at Civic Health Partners, an organization she founded after 15 years leading Health Impact at Consumer Reports. As a coach, speaker, and writer, she guides leaders through the discovery of ethical solutions and trust-building strategies that integrate empathy and evidence.